Month in Review: February 2026

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

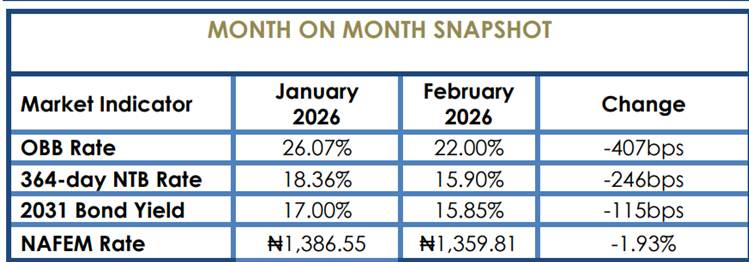

February was marked by active liquidity management, with system balances remaining structurally in surplus despite fluctuations from OMO and NTB maturities, coupon payments, and FAAC inflows. Treasury bills saw robust demand, driven by primary market activity and reinvestment flows, while the OMO segment offered higher yields for short-duration exposure. The FGN bond market traded constructively, led by mid-tenor bonds (2031–2035), with strong auction results and a 50bps MPR cut supporting yield compression of 100–120bps by month end. In the FX market, the naira experienced moderate volatility, initially weakening before strengthening on foreign inflows and Central Bank interventions, closing at ₦1,355.37/$. Overall, market sentiment remained constructive, underpinned by strong liquidity, sustained investor demand, and policy support.

MONEY MARKET REVIEW

Liquidity conditions in the money market fluctuated throughout February, largely influenced by the timing of OMO and NTB maturities, auction settlements, bond coupon payments, FAAC inflows, and primary market repayments. Although system liquidity remained in surplus for the entirety of the month, notable tightening episodes emerged when large OMO and NTB auction settlements outweighed inflows. Overall, the market reflected an environment of active liquidity management, with operations by the Central Bank of Nigeria playing a central role in shaping system balances.

Key Metrics

- Opening System Liquidity – ₦596.47 billion

- Closing System Liquidity – ₦3.75 trillion

- Net Liquidity Change – ₦3.15 trillion expansion

- Average OBB Rate – 22.00%

- Average Overnight Rate – 22.25%

- Intra Month OBB Range 2- 2.60% to 22.00 %

Market Performance

Liquidity opened the month in surplus at ₦596.46 billion, recovering from early pressures from OMO auction settlements and CRR debits. In the first week, ₦1.03 trillion in OMO maturities lifted system balances to ₦2.57 trillion. By the second week, continued OMO inflows of ₦993.00 billion further strengthened liquidity to ₦4.32 trillion, marking the month’s peak.

Mid-month, system balances tightened sharply to ₦1.89 trillion due to ₦2.30 trillion in OMO auction settlements, ₦1.91 trillion in NTB repayments, and ₦765.89 billion in primary market settlements, before rebounding to ₦2.16 trillion on subsequent OMO inflows. In the final week despite bond and OMO auction settlements debits, ₦614.61 billion in OMO maturities, ₦650.50 billion in bond coupon payments, and FAAC disbursements restored liquidity, with the month closing at ₦3.75 trillion.

Despite pronounced intra-month swings driven by primary market activity, the financial system remained structurally in surplus throughout February.

Summary

February reinforced the dominant role of primary market operations in driving money market liquidity. While recurring maturities and fiscal inflows provided consistent liquidity injections, auction-related debits introduced temporary volatility and tightening episodes. Nonetheless, the system maintained a structurally surplus position throughout the month, underscoring effective liquidity management and strong reinvestment support.

FIXED INCOME MARKET REVIEW

The fixed income market traded on a progressively constructive tone during the month, supported by strong auction demand, robust system liquidity, and active secondary market repositioning. Both the Nigerian Treasury Bills (NTBs) and Open Market Operations (OMO) segments recorded significant investor participation, with subscription levels consistently exceeding offer sizes at primary auctions.

Key Metrics

91-day NTB

- Opening Rate – 15.84%

- Closing Rate – 15.80%

182-day NTB

- Opening Rate – 16.65%

- Closing Rate – 16.65%

364-Day NTB

- Opening Rate – 16.98%

- Closing Rate – 15.90%

Market Performance

Treasury bills traded on a demand-driven note during the month, with activity largely influenced by Primary Market Auctions and subsequent secondary market repricing.

Key maturities such as the 4 Feb 2027, 18 Feb 2027, 7 Jan 2027, and 21 Jan 2027 dominated flows throughout the month.

- The 4 Feb 2027 NTB began trading around 15.85%/15.65%, later repricing to close around 16.25%/16.00% earlier in the month before compressing toward 15.85%/15.65%.

- The 18 Feb 2027 NTB, introduced mid-month, traded around 15.70%/15.60% and later moderated to approximately 15.40%/15.10%, with transactions seen near 15.30% before closing at 15.75%/15.60%.

The OMO segment maintained a yield premium over NTBs and remained the preferred instrument for investors seeking higher returns and short duration exposure.

- The 26 May 2026 traded around 19.40%/19.00%, later adjusting to 19.70%/19.20%, before moderating toward 19.15%–19.30% levels and the closing at 19.40% offer.

- The 2 June 2026 traded around 19.40%/19.30%, later compressing toward 19.00%–18.55% and closing at 20.20%/19.50%

Longer-dated OMOs such as 12 Jan 2027 and 19 Jan 2027 were quoted around 17.20%/17.05% earlier in the month before compressing toward 16.15%/16.00% and 16.88% bid.

- The 11 Aug OMO traded around 18.70%/18.50%. Select short-dated OMOs such as 5 May 2026 traded as high as 21.00%/20.00% post-auction.

Summary

The Fixed income market closed the month on a firm note, underpinned by strong auction demand and supportive liquidity conditions. Persistent oversubscription at primary auctions signalled sustained investor appetite, particularly for longer dated instruments, which drove yield compression at the long end of the curve.

The market closed the month with improved confidence, sustained investor participation, and a structurally firm demand backdrop across both NTB and OMO segments.

FGN BOND MARKET REVIEW

The FGN bond market experienced a dynamic month, beginning with cautious positioning before transitioning into a more bullish phase towards the month’s end. Early trading was influenced by liquidity dynamics, inflation data, and issuance expectations. As the month progressed, strong auction outcomes and monetary policy easing helped restore confidence, encouraging selective demand, particularly within the mid-tenor segment. By month-end, the market had shifted from defensive positioning to stronger demand-led activity.

2031 Bond

- Opening Yield – 16.90%

- Closing Yield – 15.90%

2032 Bond

- Opening Yield – 16.75%

- Closing Yield – 15.77%

2034 Bond

- Opening Yield – 16.80%

- Closing Yield -15.65%

2035 Bond

- Opening Yield – 16.80%

- Closing Yield – 15.83%

Market Performance

Trading in February was primarily focused on mid-tenor bonds, especially the 2031–2035 maturities, while short- and long-term bonds remained relatively subdued. Early in the month, modest demand led to slight yield compression, with Feb 2031, Jun 2032, May 2033, Feb 2034, and Jan 2035 bonds trading between 16.90%–16.65%, and average benchmark yields rising slightly by 10bps in the first week. Mid-week, improved interest in the mid-tenor segment compressed yields to 16.65%– 16.40%.

January inflation data and the February issuance circular (₦900 billion across 2032–2034 reopenings) spurred bullish momentum, with yields on key mid-tenor bonds declining 45bps to 16.60%–16.25% ahead of the OMO auction. Liquidity tightening from OMO and NTB settlements later tempered 2031 Bond Opening Yield Closing Yield 16.90% 15.90% 2032 Bond Opening Yield Closing Yield 16.75% 15.77% 2034 Bond Opening Yield Closing Yield sentiment, causing yields to edge slightly higher to 16.30%–16.05%.

The Debt Management Office’s February bond auction was a turning point. Total subscriptions of ₦2.70 trillion against an offer of ₦800 billion resulted in ₦524.27 billion allotted at lower stop rates— 15.74% for 2032s and 2033s, 15.50% for 2034s. Following the auction, mid-tenor bonds rallied, with Jun 2032 at 15.60%/15.35%, May 2033 at 15.30%, and Feb 2034 at 15.40%/15.30%, driving average benchmark yields down by ~50bps from early month levels.

The Monetary Policy Committee’s 50bps reduction in the MPR to 26.50% further supported investor confidence. By month-end, mid-tenor yields had declined 100–120bps relative to opening levels, with Feb 2031, Jun 2032, May 2033, Feb 2034, and Jan 2035 trading around 15.90%–15.50%, reflecting strong auction absorption, robust demand, and supportive policy and liquidity dynamics.

Summary

February highlighted the resilience of the FGN bond market amid elevated supply and shifting liquidity conditions. Strong auction demand, easing policy signals, and sustained reinvestment flows played a pivotal role in driving yield compression. Consistent concentration of activity within mid-tenor bonds confirms investor preference for balanced duration exposure and liquidity. While intermittent volatility emerged during liquidity tightening phases, overall market direction remained constructive toward month-end.

FOREIGN EXCHANGE MARKET REVIEW

The FX market traded on a dynamic but liquidity-driven tone throughout the month, shaped primarily by fluctuations in Foreign Portfolio Investor (FPI) inflows, demand pressures, and intermittent Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) intervention. Market direction alternated between strong appreciation phases supported by offshore inflows and corrective depreciation episodes driven by profit-taking, risk-off positioning, and temporary supply constraints.

- Opening NAFEM Rate – ₦1,390.36 per Dollar

- Intra month Range – ₦1,335.96 to ₦1,390.36

- Closing NAFEM Rate – ₦1,359.81 per Dollar

- Monthly Movement – 4.1% appreciation

Market Performance

The naira began the month under pressure, weakening to around ₦1,390.36/$ at the NFEM window amid strong demand and wide spreads. Improved FX supply from FPIs and CBN intervention subsequently drove a sharp appreciation phase, with the currency strengthening to approximately ₦1,358.28/$.

Mid-month, sustained offshore inflows kept the market largely offered, enabling further gains and improved liquidity conditions. However, intermittent profit-taking and reduced offshore supply triggered temporary reversals. Toward month-end, heightened demand pressures, limited FPI inflows, and global risk concerns tilted the market to a firmer bid tone. Despite CBN dollar sales interventions (including a $100 million injection within the ₦1,352–₦1,360 range), demand remained elevated, and the NFEM rate settled around ₦1,355.37/$, reflecting moderate month-end depreciation from intra-month highs.

Overall, the month was characterized by moderate volatility, alternating offered and bid tones, and active liquidity management by the apex bank.

Summary

The FX market closed the month, reflecting a balance between strong offshore inflows and intermittent demand pressures. Movements were largely liquidity driven, with Foreign Portfolio Investor participation serving as the primary anchor for stability and appreciation phases. Periods of reduced inflows, profit-taking, and heightened global risk sentiment quickly translated into bid-side pressure, highlighting the market’s sensitivity to shifts in supply dynamics. Central Bank interventions played a stabilizing role during episodes of elevated demand, preventing disorderly movements and restoring two-way quotes. Overall, the market demonstrated moderate volatility but remained fundamentally anchored by liquidity conditions, with near-term direction expected to continue hinging on the consistency of foreign inflows and policy support.

STRATEGIC TAKEAWAYS

- Liquidity conditions remained dynamic but manageable, driven by auction settlements, maturities, and primary market inflows.

- Treasury bills demand stayed robust, particularly for key shorthand long-dated maturities, supported by reinvestment flows and active secondary market trading.

- Bond market sentiment improved significantly toward month-end, aided by strong auction outcomes, mid-tenor focus, and monetary policy easing.

- FX stability strengthened, underpinned by foreign portfolio inflows and targeted Central Bank interventions, despite intermittent demand pressures and global risk concerns.

HERWOOD OUTLOOK

Looking ahead, liquidity dynamics and primary market activity will remain key drivers of market conditions. In the fixed income market, demand for both Treasury bills and FGN bonds, particularly mid- and long-tenor instruments, is expected to stay strong, supported by reinvestment flows and attractive yield opportunities.

In the FX market, stability will continue to hinge on consistent foreign inflows and policy support.

We remain committed to guiding clients through evolving market conditions with disciplined positioning and informed execution to optimize returns while managing risk.